Practice-based research or when research back up practices – the example of week programming in elite (soccer) football

There are many factors to consider when planning the microcycle in elite (soccer) football (1,14). Whether it’s about session content, orientation, and load, or when to rest players, there are almost as many approaches that coaches and cultures (1).

Today, the information available is based on either anecdotal reports from single clubs programming dynamics (based mainly on quantitative information, e.g., external load based on GPS) (2-11) large-scale surveys (1), or periodization guides such as those first developed by R. Verheijen (13) and later, the FC Barcelona (14).

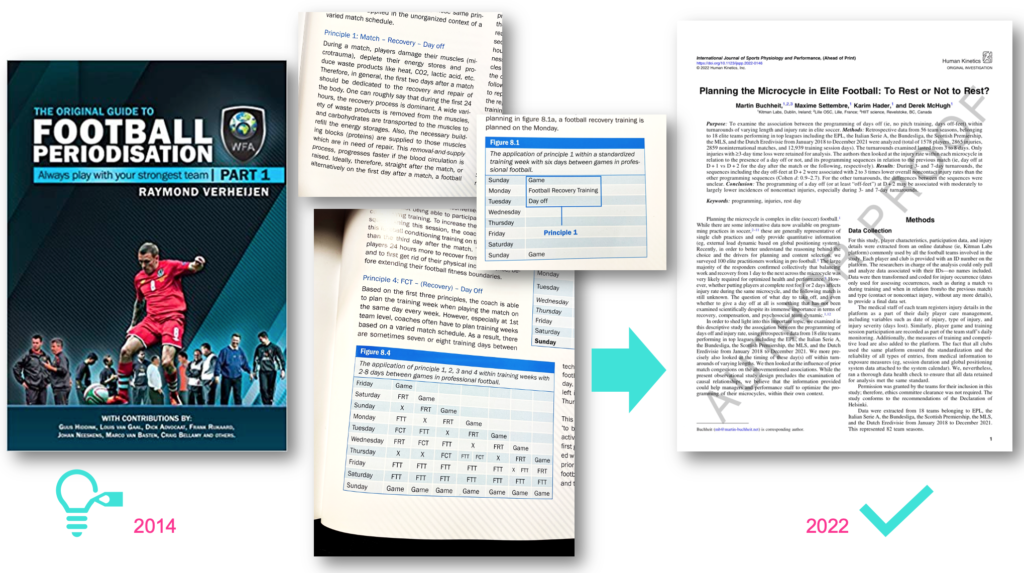

“The Original Guide to Football Periodisation – Part 1”, by R. Verheijen in 2014 (13) is the first and by far the most complete source of information on football programming. In chapter 8, he talks about his principles for week programming, where he provides clear examples of weekly microcycles. Importantly, all microcycles, irrespective of their length, start with his first principle: Match / D+1: Recovery / D+2: Day off.

While R. Verheijen principles have been adopted across the globe by thousands of practitioners, the question of what day to take off had not been examined scientifically (i.e., with data backing up practices) despite its immense importance in terms of recovery, compensation, and psycho-social team dynamic (1,12).

In order to shed light on this important topic, we examined for the first time the association between the programming of days off and injury rate, using retrospective data from 18 elite teams performing in top leagues including the EPL, the Italian Serie A, the Bundesliga, the Scottish Premiership, the MLS, and the Dutch Eredivisie from January 2018 to December 2021 (15).

While the present observational study design precludes the examination of causal relationships, and despite some variability between the different turnaround lengths, the sequences including the day off-feet at D+2 were associated with 2 to 3 times lower injury rates per day than the other sequences when the day off was programmed at D+1, or not programmed at all (at least for the 3- and 7-d turnarounds).

Training at D+1 and having a day off at D+2 may offer several advantages both on the performance and injury sides of things:

D+1 training / D+2 off

- Starters of the previous match can receive treatment at D+1 and perform their recovery session

- Benched players and substitutes also have the opportunity to train hard at D+1 to compensate for the match they didn’t play.

- Everyone to ‘close the previous turnaround cycle’ (recovery/compensation), before getting back fresh at D+3 for a new ‘cycle’ until the next match.

D+1 off / D+2 training

- Opportunities to care for starters and compensate for benched and substitute players are reduced, and potentially postponed.

- Some starters may still need some treatment at D+2 and may therefore not be able to train

- Subs may have been under a reduced training regime for 2-3 consecutive days (light load at D-1, 0 to 30 min of play max on MD, and off at D+1), disturbing an optimal training dynamic and likely limiting their overall adaptation.

Best practice is “a procedure that has been shown by research and experience to produce optimal results and that is established or proposed as a standard suitable for widespread adoption.”

Until our new research was published (15) responses to the question “ which days are best to rest?” was mainly anecdotal (1-12,14) or limited to R. Veheijen’s framework (13).

Our new practice-based research based on a very large sample size (>1800 turnarounds) within the best teams and leagues in Europe provides clear support to R. Verheijen’s framework (13) – 8 years after his transformational book was published.

It may take a bit of time, but sometimes (good) research can back up (best) practices.

#usefulresearch

References

- Buchheit, M. Sandua M, Berndsen J, Shelton, Smith S, Norman D, McHugh D and Hader K. Loading patterns and programming practices in elite football: insights from 100 elite practitioners. Sport Perf & Sci Research, 2021, V1.

- Castillo D, Raya-González J, Weston M, Yanci J. Distribution of External Load During Acquisition Training Sessions and Match Play of a Professional Soccer Team. J Strength Cond Res. 2019. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003363. Online ahead of print.

- Chena M, Morcillo JA, Rodríguez-Hernández ML, Zapardiel JC, Owen A, Lozano D. The Effect of Weekly Training Load across a Competitive Microcycle on Contextual Variables in Professional Soccer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5091. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105091.

- Clemente FM, Owen A, Serra-Olivares J, Nikolaidis PT, van der Linden CMI, Mendes B. Characterization of the Weekly External Load Profile of Professional Soccer Teams from Portugal and the Netherlands. J Hum Kinet. 2019 ;66:155-164. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2018-0054..

- Hannon MP, Coleman NM, Parker LJF, McKeown J, Unnithan VB, Close GL, Drust B, Morton JP. Seasonal training and match load and micro-cycle periodization in male Premier League academy soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(16):1838-1849. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2021.1899610.

- Los Arcos A, Mendez-Villanueva A, Martínez-Santos R. In-season training periodization of professional soccer players. Biol Sport. 2017;34(2):149-155. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2017.64588. Epub 2017 Jan 1.PMID: 28566808.

- Malone JJ, Di Michele R, Morgans R, Burgess D, Morton JP, Drust B. Seasonal training-load quantification in elite English premier league soccer players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015;10(4):489-97. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0352.

- Mateus N, Gonçalves B, Felipe JL, Sánchez-Sánchez J, Garcia-Unanue J, Weldon A, Sampaio J. In-season training responses and perceived wellbeing and recovery status in professional soccer players. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0254655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254655. eCollection 2021.P

- Martín-García A, Gómez Díaz A, Bradley PS, Morera F, Casamichana D. Quantification of a Professional Football Team’s External Load Using a Microcycle Structure. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(12):3511-3518. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002816.

- Nobari H, Barjaste A, Haghighi H, Clemente FM, Carlos-Vivas J, Perez-Gomez J. Quantification of training and match load in elite youth soccer players: a full-season study. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2021. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.21.12236-4. Online ahead of print.

- Oliveira R, Brito J, Martins A, Mendes B, Calvete F, Carriço S, Ferraz R, Marques MC. In-season training load quantification of one-, two- and three-game week schedules in a top European professional soccer team. Physiol Behav. 2019;15;201:146-156. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.11.036.

- Buchheit M. Houston, We Still Have a Problem. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12(8):1111-1114. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2017-0422.

- R. Verheijen. The Original Guide to Football Periodisation Part 1. World Football Academy, 2014.

- Tarragó JR, Massafret-Marimón ML, Seirul·lo F and Cos F. Entrenamiento en deportes de equipo: el entrenamiento estructurado en el FCB. Apunts. Educacion Fisica y Deportes. 2019 July 3(137):103-114.

- Buchheit M, Settembre M, Hader K and McHugh D. Planning the microcycle in elite football: to rest or not to rest? IJSPP, In press, 2023.