Houston, we still have a problem

M. Buchheit. Houston, we still have a problem. IJSPP, In press 2017.

Full text here

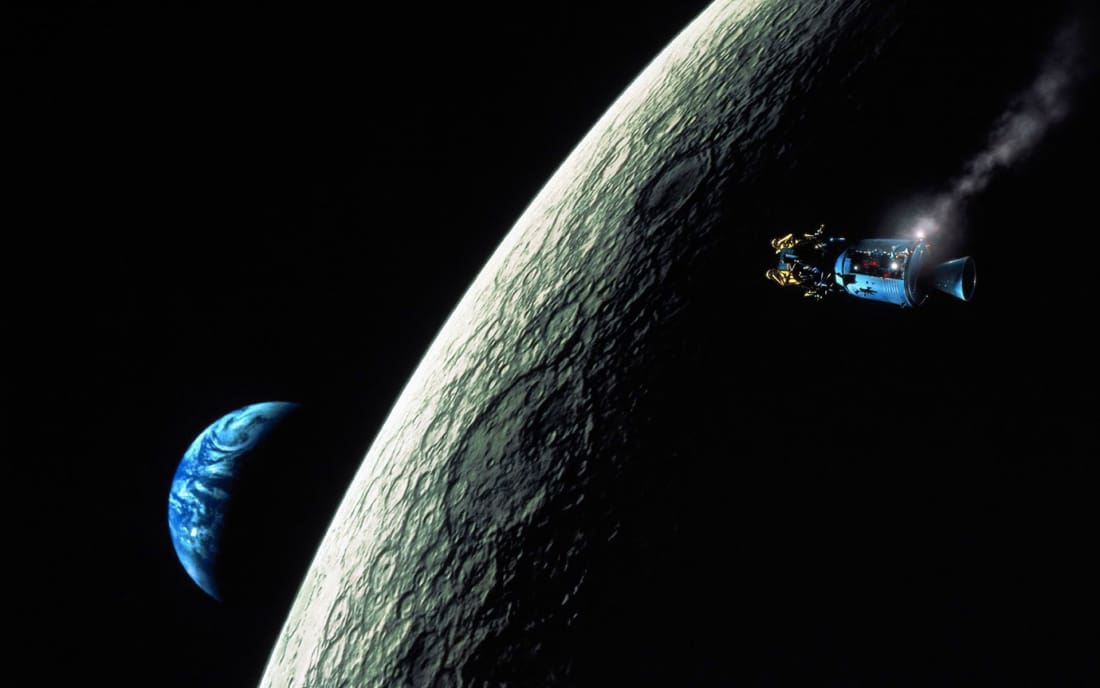

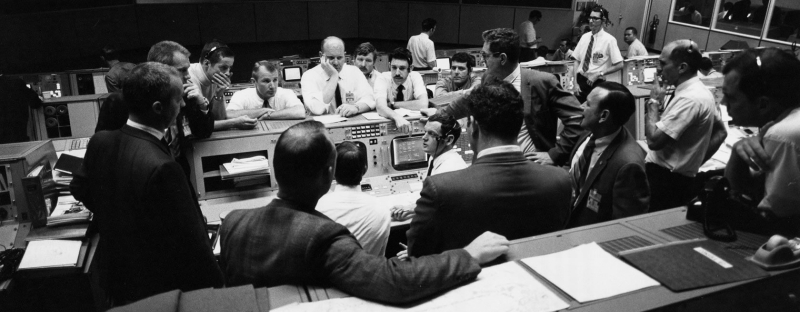

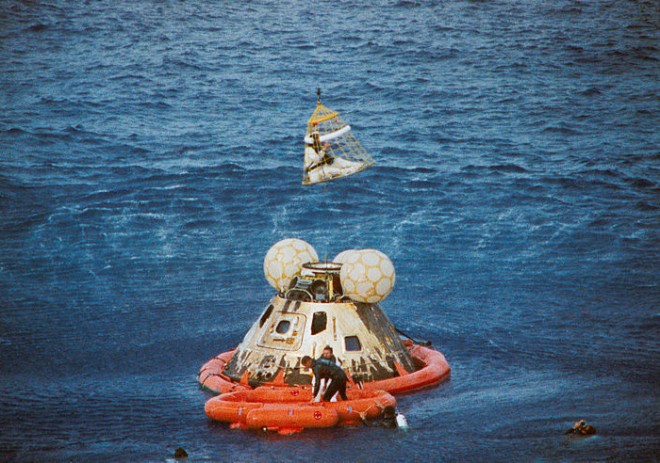

Apollo 13 was launched at 1313 Houston time on Saturday, April 11, 1970. Following months of meticulous preparation, highly-skilled and experienced commandant J.A. Lovell and his crew were on their way for the third lunar landing in the history of humanity. Apollo 13 was looking like it would be the smoothest flight ever.1 When the astronauts finished their TV broadcast, wishing us earthlings a good evening, they didn’t imagine that an oxygen tank would explode a few moments later, rendering them close to spending the rest of their lives in rotation around the planet. While the crew eventually reached Earth safely, I wished to use this well-known incident to discuss further the link, or lack thereof, between sport sciences research and current field practices.2,3 My feeling is that failure to rethink the overall research/publishing process will keep us on orbit ad aeternum. That is, the sport sciences as a field will remain only at the periphery of elite sport practice.

Sport sciences in orbit. The somewhat extreme point I want to make is that there is a feeling that the academic culture and its publishing requirements have created a bit of an Apollo 13-like orbiting world (e.g., journals and conferences) that is mostly disconnected from the reality of elite performance.2,3 For example, how many coaches read publications or attend to sport sciences conferences?4 These guys are competition beasts, so if they could find any winning advantage, why wouldn’t they read or attend these? The reality is that what matters the most for coaches and players is the outcome, which is unfortunately rarely straightforward with the sport sciences. As one example, the first thing that Steve Redgrave (5 times Rowing Olympian) asked Steve Ingham (Lead Physiologist, English Institute of Sport) was if he was going to win more medals with his scientific support.5 Likewise, the first time I offered some amino acids to Zlatan Ibrahimović (top Swedish soccer player), he asked me straight up: “are these going to make me score more goals?” Adding to the problem, support staff in elite clubs often have high egos and as recently tweeted by R. Verheijen (Dutch football coach), they often can’t distinguish between experience (which they have) and knowledge (which they don’t always have). Such workers often don’t want to hear about the evidenced-based approach that we endlessly try to promote6 and devalue the importance of sharing data.7 Personal development courses and research & development departments are perceived as a waste of time and money, or as trivial undertakings that sport scientists pursue to promote themselves. To justify such an aggressive attitude against sport sciences, they often cite poorly designed, poorly interpreted and misleading studies, which is, in effect an argument that we have to accept.

Poor research discredits our profession. Life has told me that people rarely change. However, I believe that sport science can (and should). Today, we, sports scientists, are rarely asked to land on the moon. In fact, the majority of us spend our time and energy building the spaceship. We often don’t realize that keeping our feet on earth is the only way we can make an impact.3 When we meet other sport scientists either at conferences or otherwise, we talk about papers, PhD defenses and complain about idiot reviewers that we just wrestled with. We rarely chat about winning trophies or servicing athletes. The reality we have to accept however is that most of our studies can’t help coaches or practitioners, and in fact some of our investigations are so illogical that they directly discredit our profession and keep us 36 000 km in the sky. Which conditioning coach working in a club is naïve enough to believe that muscle metabolite contents could predict match running performance, knowing the importance of contextual variables (scoreline, team formation, position-specific demands8)? Which physiotherapist could be bothered enough to look at the recovery kinetic of fatigue markers following a treadmill run, from which all field-specific muscle damaging actions have been removed? British Journal of Sports Medicine surveys often blame practitioners for not following certain interventions believed to be optimal, when in reality, personnel in the field are often implementing things that are more advanced than what the academic ‘experts’ are trying to advise. Additionally, poor use of statistics in research often leads to the wrong conclusions,9,10 which creates confusion in clubs where such benefits might be expected for individual athletes. Poor research and translation keeps us in orbit.

The research doesn’t always apply.11 There are many situations where (often successful) practitioners and athletes don’t apply what the sport sciences might suggest. Does it mean that these people are all wrong? Shall we systematically blame all practices that are not “Evidenced-Based”? With the huge quantity of research produced nowadays, it is easy to find contradictory studies. The findings from one day are often refuted the next. So what is “the evidence” in the end? Meta-analyses are likely a part of the answer, but the quality of the studies included and the profile of the populations involved can always be discussed. Shouldn’t we be more pragmatic and reconsider the importance of “best practice” instead?11 Here are some examples of clear disconnects between current practices and scientific evidence:

- There is almost no evidence that massage provides any sort of physiological recovery benefit.12 Fact: every single athlete in the world loves to be massaged after competition/heavy training.

- Beta-alanine and beetroot juice have both been shown to have clear ergogenic effects on some aspects of performance.13 Fact: the majority of athletes can’t be bothered using them for their constraining ingestion protocols (2-3 doses/day for 4-10 weeks for beta-alanine13) and awful tastes, respectively.

- Load monitoring has been shown to be key to understanding training and lowers injury risk. 14 Fact: many of the most successful coaches, teams and athletes in the world win major championships and keep athletes healthy without use of a single load monitoring system.

- The importance of sleep for recovery and performance is clearly established.15 Fact: teams often train in the morning the day following an away game, which comprises sleep, mainly for social (time with family in the afternoon) and business (sponsors operations) aspects. And they still win trophies.

- Training at the same time of the day as matches may help body clock adjustments and subsequence performance.16 Fact: Most teams train in the morning for the reasons mentioned above.

- The optimal quantity of the various macronutrients to be ingested for athletes has been described for decades.17 Fact: most elite athletes have actual nutrition practices that are substantially different to what is prescribed,18,19 and they still win trophies.

We don’t have the right answers. Here is a discussion I had with a colleague a couple of years ago while observing their cold water immersion protocol after an away match:

- MB: Hey buddy, what’s the temperature of the cold bath?

- Physio: (looking busy) 9 °C

- MB: Wow! how long do the players immerse themselves?

- Physio: 2 minutes!

- MB: hum…, thanks. 2 minutes only? Are you aware of the literature20 suggesting that it might be best if we can get them to stay for 10-15 min, with the temperature at 11-15°C instead?

- Physio: (rolling his eyes over and looking bothered) THANK YOU. With 2 bath containers and the bus leaving in 35 min, how do you want me to deal with each of the 10 players? They’ve got press interviews and selfies with the fans on their plate before we take off… what temperature do you suggest for 2 min then? And while you’re thinking of that, pass me my tape, I need to pack!

- MB: …. (In fact, as far as I know, none of the ˜300 studies on cold water immersion has addressed this specific question yet … he just sent me back to orbit!)

This discussion, together with the above-mentioned examples when research doesn’t apply show that often, instead of a “what is best”-type of answer, practitioners need a “what is the least worst option in our context”-type of answer. Do we really need to know the effect of total sleep deprivation on performance? We rather need to know if there is a difference between sleeping 8, 6 or only 4 hours but with a catch-up nap in the afternoon. Do we really need to know the effect of a 6-week hypoxic training intervention using repeated all-out cycling efforts 3 times/week, while in most soccer clubs conditioning is systematically done with the ball on the pitch? We are likely more interested in the optimal exercise formats that should be used in the specific context of congested training and match situations. We rather need to know what is the minimum volume of high-intensity sessions necessary to keep substitute players fit. In fact, it is very likely that an academic would shot himself a bullet in the foot (or send himself to orbit) if he decides by himself the topic of a research question, simply because things are way more complex than he may think.

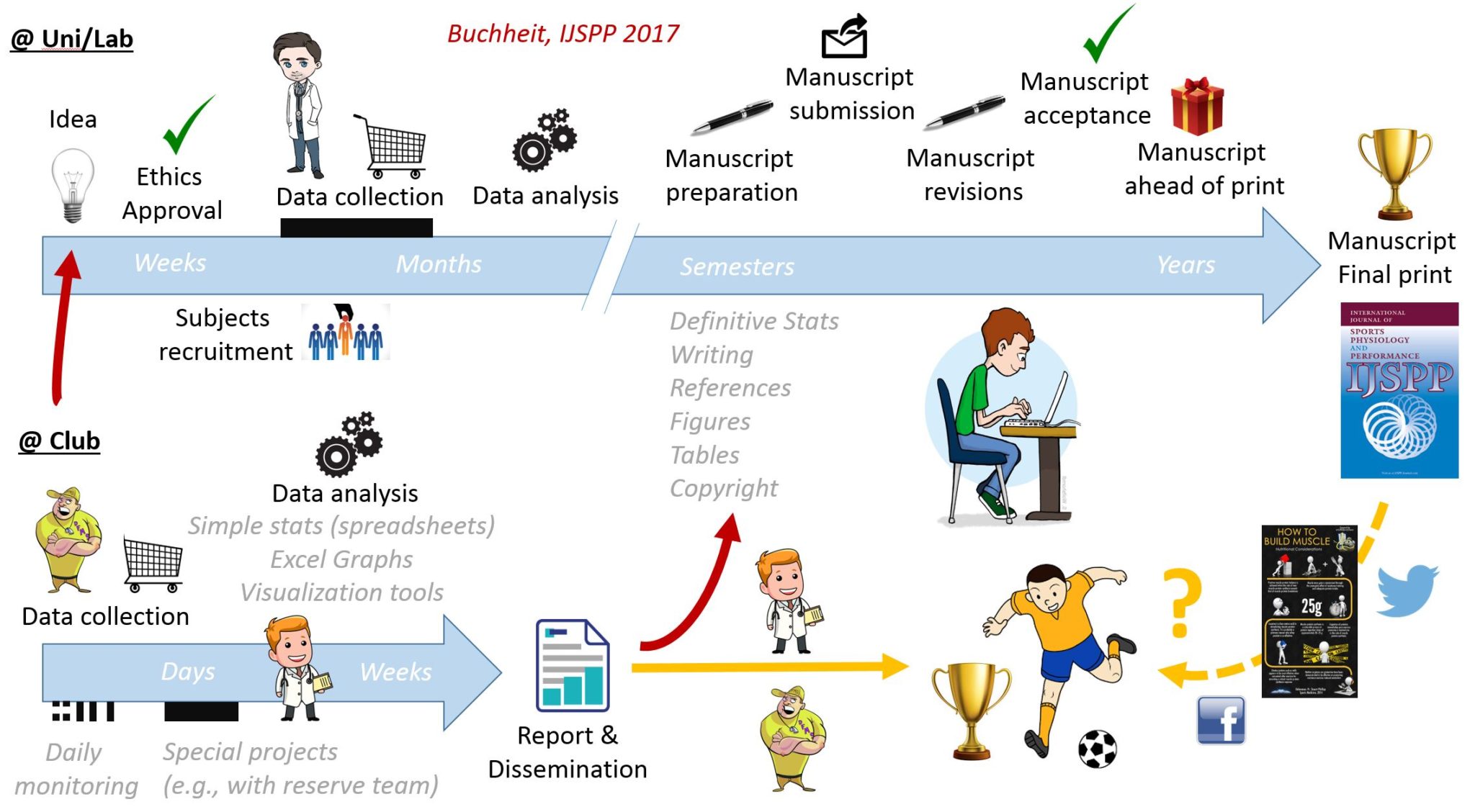

How do we bring Sport Sciences back to earth? One solution might be for us to start where the questions actually arise (i.e., in clubs or federations) and then develop the structures required to conduct applied research, through research & development departments.21-23 Such sport scientists, who attempt to apply a degree of scientific rigor in a world of beliefs,3 are more than capable of creating relevant knowledge and best practice guidance within only a few weeks (Figure 1). This model contrasts with academic research that takes years to reach publication, before remaining inaccessible to the majority of coaches, athletes and practitioners (e.g., paper format,4 cost of journal subscription24). However, this type of in-house research can’t be the only research model for at least two reasons. First, club scientists don’t always have the opportunity (population, materials, skills, funding) to investigate the questions they are asking (e.g., should players sleep for 6 or 4 + 2 h following games?). Second, the knowledge that club scientists produce, if any, remains generally inside the clubs. While this is sometimes intentional (trying to keep a competitive advantage over the opposition), often club scientists have neither the need nor the skills and time to publish papers. For club practitioners, their mission is to improve club practices. A better use of their time is to multiply in-house data analyses/research projects than writing papers. Additionally, given the heavy requirements of peer-reviewed research (ethical approval, need for balanced study designs, control of external variables, large sample sizes, submission processes and reviewing battles), only the tip of the iceberg work ends up being published. In order for the rest of the iceberg to be disseminated outside of the club in the name of science, an option might be to offer shorter submission formats that are more accessible for busy club scientists, i.e., extended abstracts with figures, which is more or less what most people only have time to read anyway. Case studies, which reflect more the type of data and interest of club practitioners, should also be promoted. Editors should also encourage authors to adjust their data for confounding variables when possible, which can help to account for the noise related to real-life data collection. For larger-scale projects, clubs must strengthen their links with universities so that their data can be analyzed appropriately, and full papers can be written by academics with the time, experience and club level understanding. Similarly, experiments that can’t be conducted at the club level can be continued and refined in the laboratory environment. Only the latter conducted ‘academic’ studies may find their relevance in the real world of applied sport. Nevertheless, even with such a club-university partnership, it may not be as smooth as it looks. The ‘most rejected paper’,25 which was only published because we paid for it (7 rejections, despite the elite population, the robust study design, the data analysis and variables measured including hemoglobin mass and performance) illustrates the failure of the overall publishing process26 and the difficulties of publishing 100% club-driven research. It is also worth noting that by the time a ‘club paper’ is published, the coaching staff have likely already been replaced, a fact that may limit return on investment.

Figure 1. Possible research processes both in Universities/Laboratories and Clubs/Federations. In addition to its likely increased relevance, the ‘delivery time’ is much faster for club/federation- vs. university-driven research. See a Club/Uni collabortion example (among others thankfully) that fits the model

Conclusion. To conclude, if we as sport scientists want to have a word to say about the game that matters, we need to work towards keeping our feet on the earth and produce BETTER research; research tailored toward practitioner needs rather than aimed at being published per se. For such research to find its audience, we probably need to rethink the overall publishing process, starting with promotion of relevant submission types (e.g., short paper format types, short reports, as provided by IJSPP or the new web platform “Sport Performance & Science Reports”27), improving the review process (faster turnaround, reviewers identified to increase accountability and in turn, review quality), and media types (e.g., free downloads, simplified versions published into coaching journals, book chapters, infographics, dissemination via social media).24 Once these first steps are achieved, and only after, club sport scientists may then be in better position to personally transfer research findings to staff and/or educate athletes.3 When it comes to guiding practitioners and athletes, instead of using an evidence-based approach, we’d rather promote an “evidence-lead” or “informed practice” approach; one that appreciates context over simple scientific conclusions.11

Acknowledgements. Sincere thanks to Paul Laursen and David Pyne for their insightful comments on drafts of the present manuscript.

References

- Lovell, J.A., Houston, we’ve had a problem. Apollo expeditions to the moon. https://science.ksc.nasa.gov/history/apollo/apollo-13/apollo-13.html 1975.

- Burke, E.R., Bridging the gap in sports science. Athletic Purchasing and Facilities, 1980;4(11):24-15.

- Buchheit, M., Chasing the 0.2. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2016;11(4):417-418.

- Reade, I., R. W., and N. Hall, Knowledge transfer: How do high performance coaches access the knowledge of sport scientists? Int J Sport Sci Coach, 2008;3(3):319-334.

- Ingham, S.A., How to support a champion: The art of applying science to the elite athlete, ed. Simply Said. 2016.

- Sackett, D.L., Protection for human subjects in medical research. JAMA, 2000;283(18):2388-9; author reply 2389-90.

- Rolls, A., No more poker face, it is time to finally lay our cards on the table. Bjsm blog, http://blogs.Bmj.Com/bjsm/2017/03/06/no-poker-face-time-finally-lay-cards-table/. 2017.

- Carling, C., Interpreting physical performance in professional soccer match-play: Should we be more pragmatic in our approach? Sports Med, 2013;43(8):655-63.

- Buchheit, M., The numbers will love you back in return-i promise. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2016;11(4):551-4.

- Buchheit, M., Does beetroot juice really improve sprint and high-intensity running performance? – probably not as much as it seems: How (poor) stats can help to tell a nice story. Https://martin-buchheit.Net/2017/01/04/does-beetroot-juice-really-improve-sprint-and-high-intensity-running-performance-probably-not-as-much-as-it-seems-how-stats-can-help-to-tell-a-nice-story/. 2017.

- Burgess, D.J., The research doesn’t always apply: Practical solutions to evidence-based training-load monitoring in elite team sports. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2017;12(Suppl 2):S2136-s2141.

- Poppendieck, W., et al., Massage and performance recovery: A meta-analytical review. Sports Med, 2016;46(2):183-204.

- Burke, L.M., Practical issues in evidence-based use of performance supplements: Supplement interactions, repeated use and individual responses. Sports Med, 2017;47(Suppl 1):79-100.

- Blanch, P. and T.J. Gabbett, Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute:Chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. Br J Sports Med, 2016;50(8):471-5.

- Fullagar, H.H., et al., Sleep and recovery in team sport: Current sleep-related issues facing professional team-sport athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2015;10(8):950-7.

- Chtourou, H. and N. Souissi, The effect of training at a specific time of day: A review. J Strength Cond Res, 2012;26(7):1984-2005.

- Burke, L.M., The complete guide to food for sports performance: Peak nutrition for your sport. 1996: Allen & Unwin; Second edition edition.

- Bilsborough, J.C., et al., Changes in anthropometry, upper-body strength, and nutrient intake in professional australian football players during a season. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2016;11(3):290-300.

- Burke, L.M., et al., Guidelines for daily carbohydrate intake: Do athletes achieve them? Sports Med, 2001;31(4):267-99.

- Machado, A.F., et al., Can water temperature and immersion time influence the effect of cold water immersion on muscle soreness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med, 2016;46(4):503-14.

- Coutts, A.J., Working fast and working slow: The benefits of embedding research in high performance sport. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2016;11(1):1-2.

- McCall, A., et al., Can off-field ‘brains’ provide a competitive advantage in professional football? Br J Sports Med, 2016;50(12):710-2.

- Eisenmann, J.C., Translational gap between laboratory and playing field: New era to solve old problems in sports science. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, 2017;2(8):37-43.

- Barton, C., The current sports medicine journal model is outdated and ineffective. Aspetar – Sports Medicine Journal, 2017;7:58-63.

- Buchheit, M., et al., Adding heat to the live-high train-low altitude model: A practical insight from professional football. Br J Sports Med, 2013;47 Suppl 1:i59-69.

- Buchheit, M., The most rejected paper -heat + altitude, accepted- illustrates the failure of the publication process https://martin-buchheit.Net/2013/09/13/adding-heat-to-the-live-high-train-low-altitude-model-a-practical-insight-from-professional-football/. 2013.

- Sport Performance & Science Reports. https://sportperfsci.com/