Applying the acute:chronic workload ratio in elite football: worth the effort?

Buchheit M. Applying the acute:chronic workload ratio in elite football: worth the effort? Br J Sports Med. 2017 Sep;51(18):1325-1327.

Full text here

The use of the acute:chronic workload ratio (A/C) has received a growing interest in the past two years to monitor injury risk in a variety of team sports.[1 2] This ratio is generally computed over 28 days (i.e., load accumulated during the current week / load accumulated weekly over the past 28 days), using both internal (session-rate of perceive exertion (Session-RPE) x duration) and external (tracking variables, often GPS-related, such as high-speed running and acceleration variables) measures of competitive and training load. While the potential benefit of such a metric is straight forward for practitioners, there remain several limitations to 1) the assessment of relative external load and in turn, injury risk in players differing in locomotor profiles and 2) the effective monitoring of overall load across all training and matches throughout the year. In turn, these limitations likely compromise the usefulness of the A/C ratio in elite football (soccer).

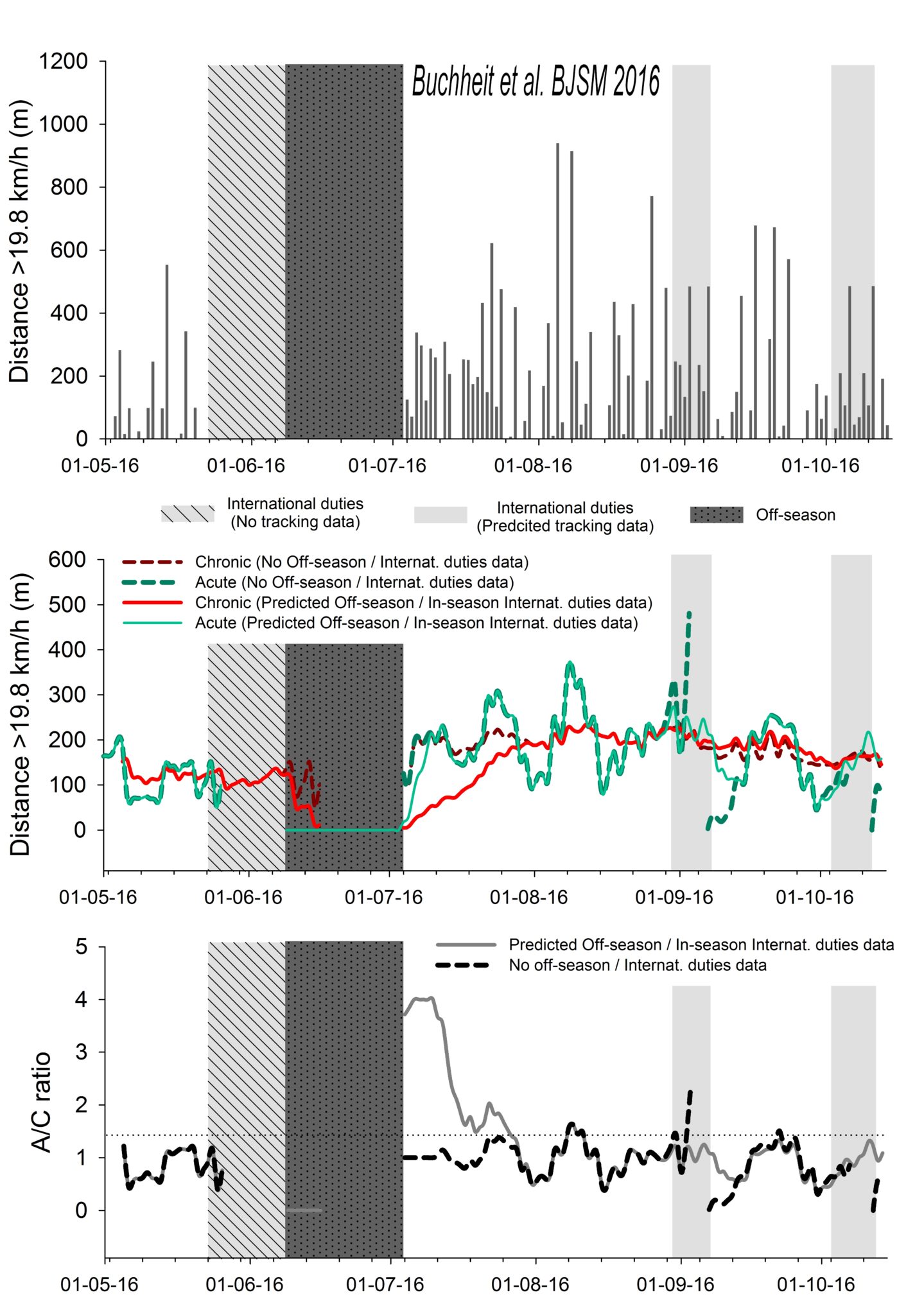

Figure 1. Daily distance (top panel) ran above 19.8 km/h by an international player (French Ligue 1) during a 6-month period (with matches and training data integrated [5]) and associated 28-d chronic and 7-d acute workloads (middle panel) and their ratio (bottom panel). The player was selected with his national team to prepare for the Euro 2016 (21/05/2016 to 08/06/2016) but wasn’t selected to participate to the final tournament. He then took ̴3 weeks of rest before starting the pre-season with his club (04/07/2016). Since the national team staff didn’t use GPS, there are no running data available during his Euro preparation. We then assumed that during his holidays, whatever the sporting activities he practiced, he was very unlikely to reach a running speed >19.8 km/h – high-speed load is therefore set at “0 distance” for these 3 weeks. Note that in-season, national team training and competitive loads have been predicted using players’ historical club data (based on training schedules and match playing times). As a consequence, the predicted running distance of the 4 matches played with the national team (2 per international break) are similar. While this may be seen as a limitation given the usually large (>15-20%) match-to-match variations in high-speed running, this approach allows at least to produce the A/C ratio through these periods while avoiding erroneous spikes/drops. Finally, these data illustrate also nicely the limitation of the A/C ratio during the pre-season period when no off-season data are available. With no off-season data (which differs from “0 distance”), chronic and acute loads are mathematically defined as similar for the first 7 training days, which results in an unrealistic A/C of 1!? The use of predicted off-season data draws fortunately a much more realistic picture, with a ratio >4 at the start of the pre-season, which decrease as training, and in turn fitness progresses.