Whom do we publish for? Ourselves, or others?

M. Buchheit. Whom do we publish for? Ourselves, or others? IJSPP ahead of print, August 18th

See also this excellent infographic based on the related paper "Chaos in the brickyard" from Forsher in 1963!!

I had been admiring his work for more than a decade, but the first time I met Pietro Enrico Di Prampero in person wasn’t until 2010 at the Football French National Federation. Our Research Unit invited Dr Di Prampero to discuss the premise of the metabolic power concept with all our staff. Prior to his formal talk, we had the chance to spend some informal time together sharing a nice lunch. During our discussion, I’ll forever remember his responses to a series of short questions:

Me: “Hey, Pietro. Many of your papers have been cited more than 600 times, and your H-index is off the chart. Obviously in academic terms, you’re a rock star. So what’s the paper you’re the proudest of?

PE Di Prampero: “… thanks… but I really don’t know. In fact, I’m not exactly sure what you mean… citation counts? H- what? Martin, I have simply tried to put on paper what I though was correct and helpful for our community… the rest really doesn’t matter, right?”

Me: “…. Well…. Sure…I guess…. “

In the current ‘publish or perish’ academic research landscape, such discussion may sound completely bizarre. Today, bulimic academics (me included) list every publication ever authored on their personal websites, advertise their Google Scholar page with their H-index in their CV, and share copies of paper acceptance notification on social media (often without any content). Many prioritize quantity, using various strategies (“Hey, I am sure that with these data we can do another cool paper”, or “Let’s form an alliance with other researchers to increase our publication rate”), over quality and substantial contribution to the field.

A crucial question for all of us today then remains. What is the motive behind our drive for publishing? Where is the ‘why’?1, 2 Are we doing this to increase our academic profile? Or are we truly trying to bring something new and useful to practitioners? Are we doing this for us, or for others and our field as a whole? As editors, we lose count of the number of times we are asked by students concerning the status of a paper that they “critically need published in order to complete their PhD due in three weeks”. While asking this question doesn’t mean the paper can’t be part of something bigger, often these motivations are not in line with what they should be.

Following previous IJSPP editorials on the importance of understanding the real needs of practitioners,3 asking the right questions and generating relevant research4 to bridge the gap between science and practice,5-7 one of the most important issues to keep in mind when producing a paper is that it should be ‘usable’, and allow effective translation of the findings to the field. The great Aaron Coutts recently insisted on the importance of clearly writing the practical applications section of a manuscript.8 But what about the actual study design, the data presentation and analysis?

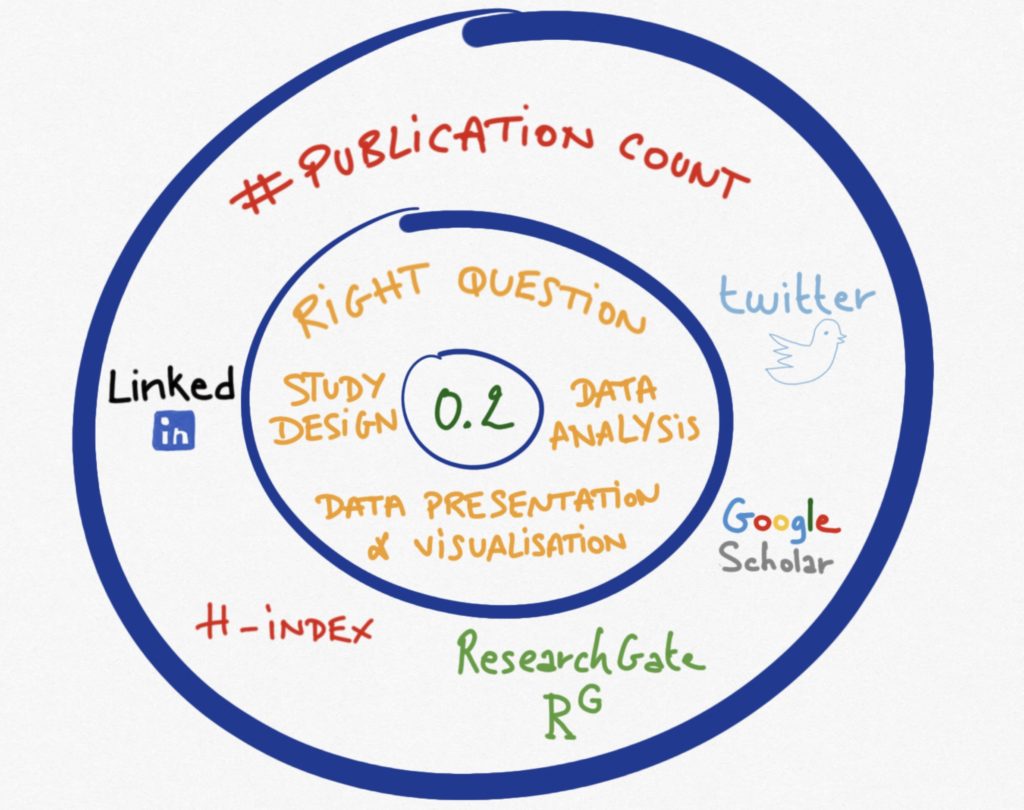

Figure 1. S. Sinek’s golden circle2 adapted to the publishing process. The ‘why’ in the centre (with ‘0.2’ referring to having an impact, as per the so-called smallest worthwhile change concept3), the ‘how’ (answering the right questions via appropriate approaches and methods) and the ‘what’ in the outer circle (publications and academic profiles).

Too often, researchers end up compromising the potential applicability of their study to increase its chances of being published. This includes ensuring that “there will be some results” (they look for large magnitude effects and a large enough sample size to mechanically reach their small ‘p’ value), oversimplifying intervention protocols to gain ‘control and feasibility’, and sometimes partially masking or cherry-picking data to make the paper ‘suitable’ for publication. While such strategies are effective in terms of publication probability, this systematically prevents the reader from finding relevant information that will assist practitioners, coaches and athletes. As an example, practitioners would be interested in knowing the individual physiological and psychological responses to partial sleep deprivation following an away match. This is complex context, as it includes stress related to the match, flights, sub-optimal nutrition before sleeping from 6 to 10 am, etc. To tackle this question, researchers have typically examined the effect of complete sleep deprivation in a lab and reported group average responses (bar graphs and no individual responses shown9).

Of course, reproducing an exact real-life scenario is challenging, but there remain elements that must be considered, even though they may reduce the likelihood of paper acceptance. We need to be clear on what we want when it comes to publishing. If it’s having an impact that is meaningful,3 that is, a real effect on the field of sport performance, we (as researchers, reviewers and editors) need to understand that less controlled real-life scenarios, but ones that are appropriately-analysed and presented, are very likely more relevant than studies that are laboratory-based with poorly interpreted data.4

If you were to ask a book editor for tips on writing the book you wanted to write, they would start by suggesting you to be clear on: 1) why do you want to write it, 2) are you sufficiently experienced and knowledgeable to write it based on your background, 3) what is it going to bring to the current literature and field of understanding, and then 4) who is your audience? This applies 100% to our field as well (see Figure 1). More often, we as researchers need to ask ourselves why, how, what, and more importantly, who we are publishing this for. Is it for ourselves, or others? Is it for science and understanding, or for improving our LinkedIn and ResearchGate profiles? Of course, the response is likely (and should be) ‘for both’. While generating better research outcomes oriented at improving our field of knowledge will benefit the researcher, publishing selfishly for the sake of publishing compromises the relevance of manuscripts needed to reach our objective and won’t take us anywhere. The latter initiative makes more noise and hides the important signal.

Clearly, the giants in our field became who they are because they produced top quality seminal papers. Unwavering in their ethics, they did not compromise their methods or ideas to satisfy reviewers and journal editors. They showed less hubris and more humility.10 It’s time for us to think of others first again.

Martin Buchheit

Associate Editor IJSPP

References

- Clubb, J., Starting with Why in Sports Science. Sports Discovery Blog, http://sportsdiscovery.net/journal/2018/05/06/starting-why-sports-science-golden-circle/. May 6, 2018.

- Sinek, S., Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. 2009: Portfolio.

- Buchheit, M., Chasing the 0.2. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2016; 11(4): 417-418.

- Buchheit, M., Houston, We Still Have a Problem. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2017; 12(8): 1111-1114.

- Haugen, T., Key Success Factors for Merging Sport Science and Best Practice. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2019: 1.

- Sandbakk, Ø., Let’s Close the Gap Between Research and Practice to Discover New Land Together! Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2018; 13(8): 961.

- Chamari, K., The Crucial Role of Elite Athletes and Expert Coaches With Academic Profiles in Developing Sound Sport Science. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2019; 14(4): 413.

- Coutts, A.J., Building a Bridge Between Research and Practice-The Importance of the Practical Application. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2020; 15(4): 449.

- Clubb, J., Why we Need to Rethink using Bar Graphs. Sports Discovery Blog, http://sportsdiscovery.net/journal/2020/07/02/why-we-need-to-rethink-using-bar-graphs/. July 2, 2020.

- Foster, C., Sport Science: Progress, Hubris, and Humility. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2019; 14(2): 141-143.

Acknowledgements. Warm thanks to the irreplaceable Paul B. Laursen (HIITScience and AUT University, Auckland, New Zealand) for his comments on a draft of the manuscript.