Does beetroot juice really improve sprint and high-intensity running performance? – probably not as much as it seems: how (poor) stats can help to tell a nice story

Full text here

A few tweets, re-tweets and emails from colleagues have caught my attention within the last 24 hrs, all pointing toward a new study showing improvements in sprinting and high-intensity intermittent running performance after dietary nitrate supplementation (beetroot shots) (1). In the 36 team-sports players (training 5-10h a week) who volunteered for the study, significant “improvements” in 5- (2.3%), 10- (1.6%) and 20-m (1.2%) sprint times and a 3.9% “increase” in high-intensity intermittent performance were reported, after no longer than 5 days of supplementation! (1)

To all practitioners who may read both the article (1) and the present blog post, the topic is obviously highly relevant; we are all looking for various ways to improve our players’ running performance – even better if these improvements can be gained legally (no doping) and without (physical) efforts. If you can convince yourself to commit to drink daily an awful 70-ml beetroot shot for 5 days before an important competition, then you may have found a really cool and lazy way to get faster and fitter!!

However, before I began to tell (again) every player at the club (who would systematically pass on beetroot because of its taste) to finally commit themselves to drink this stuff, because it really works, I wished to make sure it would be worth the effort, both for them and me. After a deeper read of the paper, a closer look at the study design, the data analysis and the stat approach, I realized that in fact, beetroot supplementation, within the context of the present study, may not be as promising as it could be understood while only reading the title of the paper. This for at least two important reasons: 1) the somewhat limited magnitude of the “changes”, although significant and 2) the questionable study design/data analysis that doesn’t allow individual responses to be clearly accounted for and analyzed.

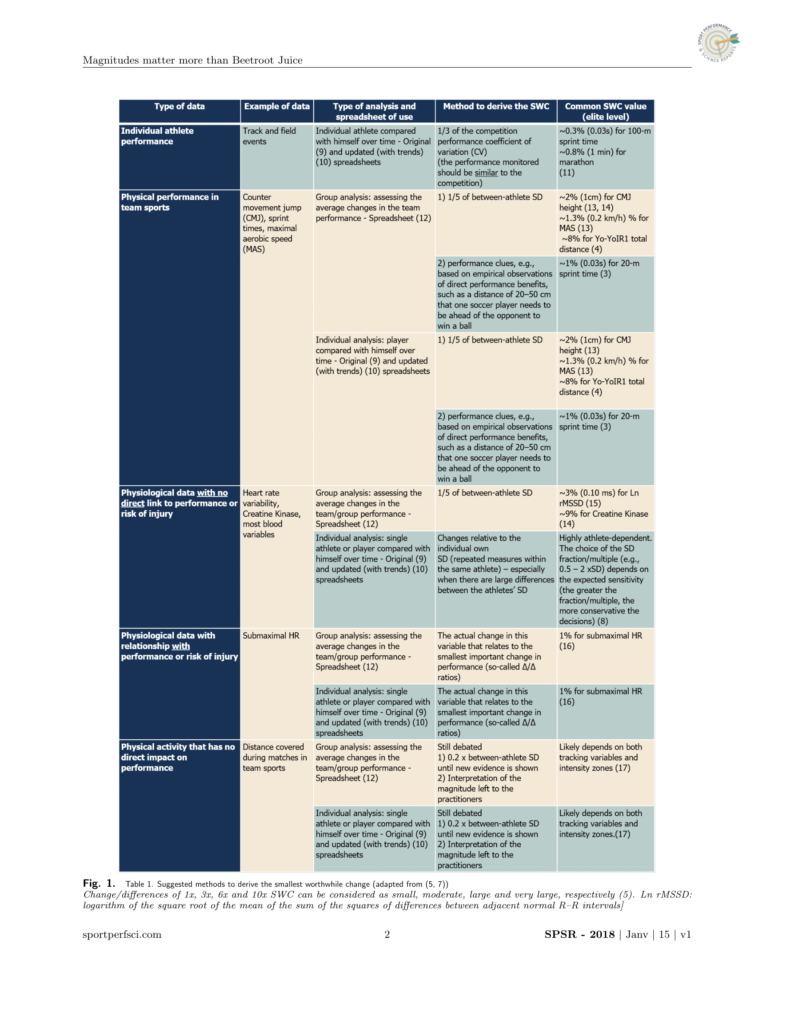

- The magnitude of the “improvement” may not be large enough to be meaningful. When considering the magnitude of the smallest worthwhile changes for different sprint distances (SWC, i.e., the minimum improvement likely to have an impact on the field, such as that required to be 20 cm ahead of an opponent to win a ball) (2), the changes reported in the present study are in fact either smaller (5 m: study 2.3% vs SWC ̴ 4%, 10 m: study 1.6% vs SWC ̴2%) or just similar to (20 m: study 1.2% vs SWC ̴1%) (2). Even for 20-m time, which magnitudes equals the SWC, chances for the “improvement” to be substantial may be no more than 50% at the individual level (when considering a typical error of the measurement (TE) of the same magnitude than the SWC – while in fact the TE may actually be twice as large as the SWC for such a distance (2), decreasing further the likelihood of a substantial change) (2). The same reasoning applies to the “increase” in Yo-YoIR1 performance (+3.9%), which SWC is generally twice larger (̴ +8% (3), +7% as 0.2xSD in the present study). In conclusion, the comparison of the reported changes, although significant, to their specific SWC directly questions the practical impact and in turn, the usefullness of beetroot supplementation in the context of the present study. These data illustrate once again that the use of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is clearly limited to assess the actual performance benefit of a supplement or an intervention (4, see the blog on the topic) – in the present case the significant P value likely results from the large sample size (n=36) – different conclusions (and probably less misleading in the present case) would be drawn with lower samples (i.e., n<15).

- The data analysis doesn’t allow individual responses to be clearly accounted for/analyzed. In fact, the authors simply chose to compare the sprints/YoYoIR1 performances following beetroot supplementation to these following the placebo drink (Post beetroot – Post placebo, via paired-samples t-tests)!? While it is not clear why such a limited approach was chosen, the proper way to analyze these data would be to look first at within-group changes, and more importantly, to compare these within-group changes (i.e., between-group differences in the changes – typical crossover design, as ‘post beetroot – pre beetroot’ compared with ‘post placebo – pre placebo’). This latter approach is way more powerful and allows the understanding of i) the effect of each treatment per se (within-group effect, in relation to the SWC), ii) the variability of the response within each treatment (SD of the change, which has important implications when using supplementation with athletes – some will respond, some not !! – and how many and by which magnitude?), iii) compare the efficacy of the treatments (differences in the magnitude of the changes) and even more importantly, iiii) compare the magnitude of the individual responses between each treatment (i.e., which treatment shows the greater variability in response). Unfortunately, all these relevant information for practitioners are missing in the manuscript.

That being said, I am happy to keep beetroot shots on the supplement table for the moment (for players that can cope with the taste… at least it hasn’t been shown to be detrimental). I may, however, not use the present study to advertise the benefit of beetroot to the players – if we want to keep our legitimacy and maintain the trust that the players put on us, I believe it is important to come to them with the right message – and in that case, applying some appropriate stats surely helps!

References

- Thompson C, Vanhatalo A, Jell H, Fulford J, Carter c, Nyman L, Bailey SJ and Jones AM. Dietary nitrate supplementation improves sprint and high-intensity intermittent running performance. Nitric Oxide 61 (2016) 55-61.

- Haugen T, Buchheit M. Sprint running performance monitoring: methodological and practical considerations. Sports Med. 2016;46(5):641.

- Bangsbo J, Iaia FM, Krustrup P. The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test: a useful tool for evaluation of physical performance in intermittent sports. Sports Med. 2008;38:37–51.

- Buchheit M. The Numbers Will Love You Back in Return—I Promise. Int J Sports Physiol & Perf, 2016, 11, 551 -554.